Tweet Review:

Players must do battle with a mutant spider and the game’s parser to save the world.

Full Review:

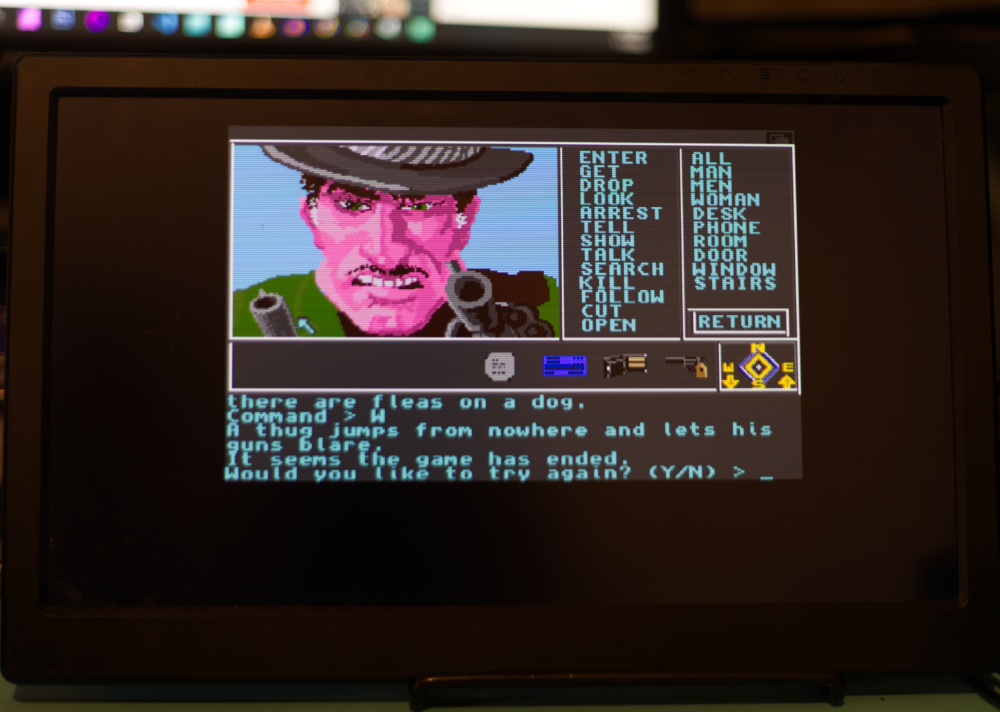

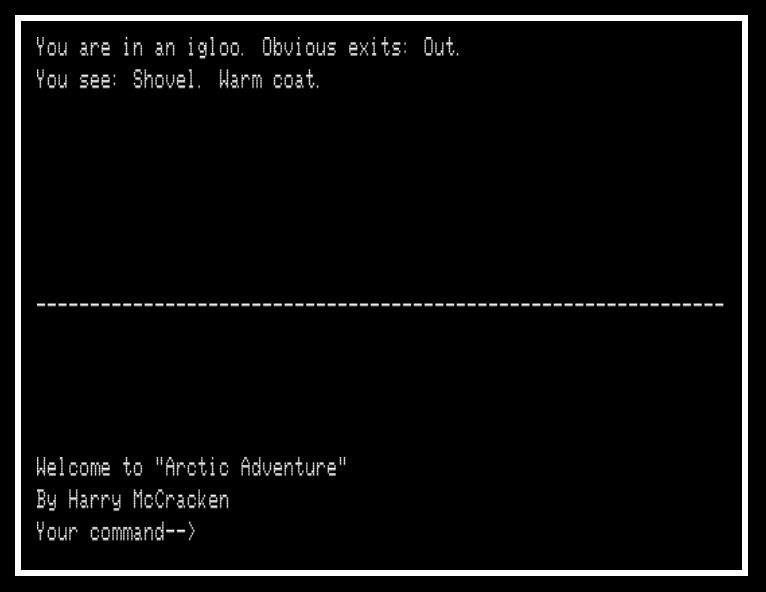

I have an unhealthy obsession with quirky, one-off text adventures from the early days of home computing. By the mid-to-late 1980s, certain norms had been adopted by the text adventure community. The ways games looked and the way players controlled them had largely coalesced by then. But the early 80s, that was the wild, wild west. Controls were kooky. Concepts were bizarre. Convincing a game’s parser to bend to your wishes was often just as challenging as a game’s puzzles. Many games from that era are dreadful to play, and yet like a moth to a bug zapper, I am attracted to them.

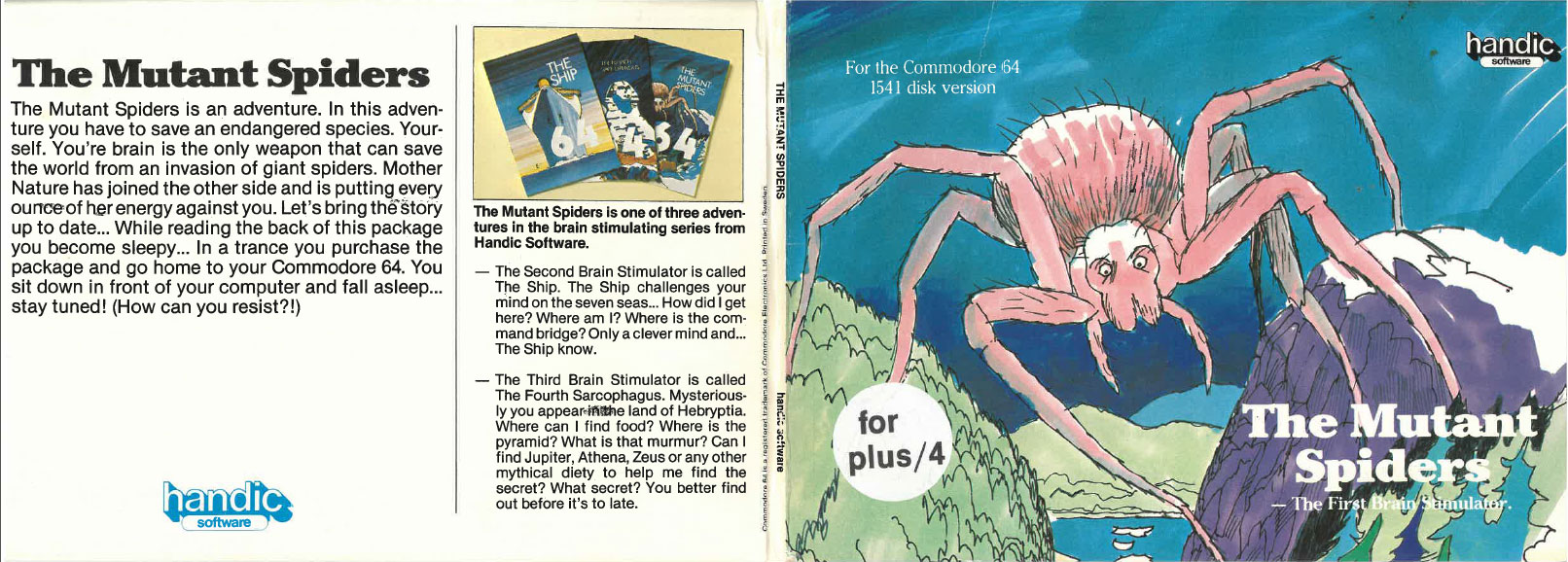

Handic Software is barely a footnote in computing history. The Swedish company was leveraged by Commodore Business Machines in the dawn of the 1980s to import Commodore computers and roughly a dozen games into the country. Within just a couple of years, Commodore established their own presence in Sweden, making Handic’s distribution system largely obsolete. From 1981 to 1983 Handic imported several early CBM releases including Gorf, Wizard of Wor, and Omega Race, while also releasing a trio of text adventures they labeled as their Brain Stimulator series. Those games included The Ship, The Fourth Sarcophagus, and this one, The Mutant Spiders.

The Mutant Spiders begins rather abruptly with a single line of text: “I wake up and find myself in a flying plane!” While this brief bit of scene setting doesn’t tell us much about the game’s overall plot, it speaks volumes about what’s in store for gamers brave enough to accept the challenge. The game’s opening line begs for an explanation, one players will never learn.

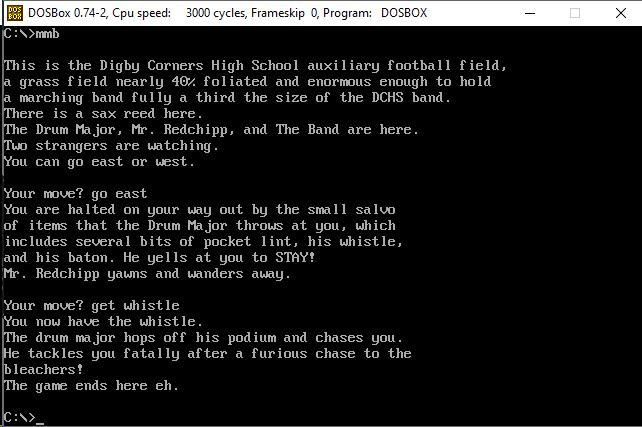

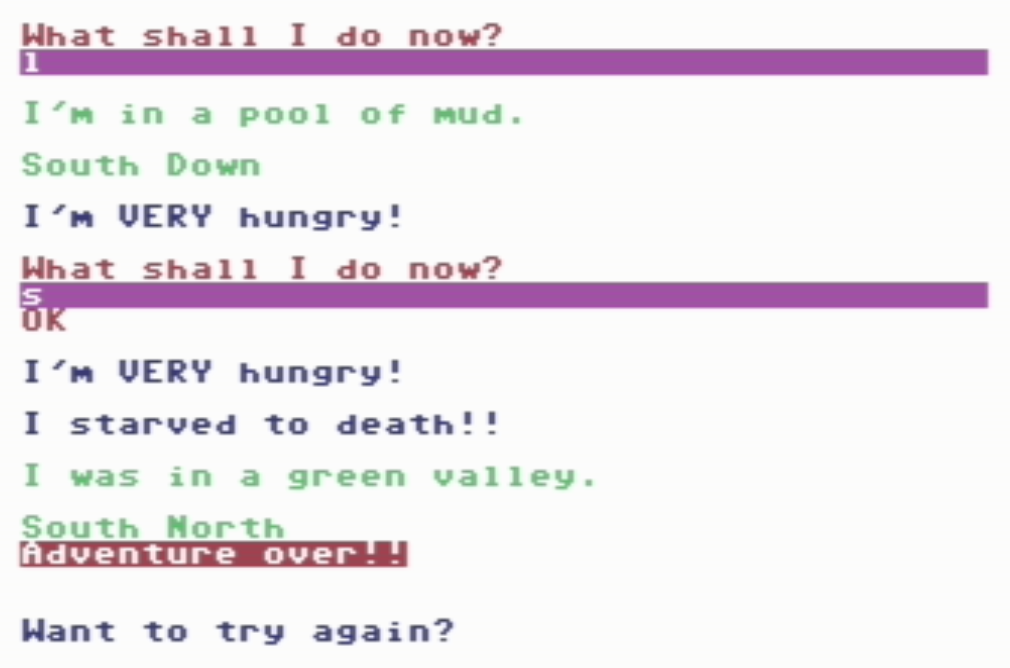

Within just a few moves it is revealed not only are we the only person on the plane — there are no other passengers or pilots — but that the plane is running out of fuel. The plane contains only a few areas to explore, and solving this first puzzle is Text Adventure 101. By doing so, we learn a lot about the game’s design. It doesn’t take long to realize the game’s engine is as rickety as the plane we’re flying on. Moving to new rooms or areas results in a simple “OK,” forcing players to type LOOK after every single move. Commands are not only occasionally obscure, but worse than that, inconsistent. (To enter the restroom, type GO DOOR. To exit, you’ll GO WEST.) The game’s parser only looks for the correct move and rarely understands anything else — on the plane you’ll discover items that can be opened, but the parser doesn’t understand the verb CLOSE. The brevity of the game’s opening line continues throughout. The plane’s cockpit has a single gauge. The bathroom contains a single item. At no point was I convinced the author of this game had ever stepped foot on an actual airplane.

But it’s not just descriptions that are lacking; it’s any sense of story logic. Why were we sleeping on a plane in the first place? What happened to the other passengers? Where is the pilot? Where’s the plane going? None of these questions (and more) are answered. These early games seem barely connected to the rich world of modern interactive fiction many of us are used to playing today. The game doesn’t just fail to fill in some story details… it doesn’t try at all.

After escaping the mysteriously unpiloted and underfueled plane, players will conveniently land next to a discarded newspaper that provides the closest thing to expository the game’s willing to offer. According to the paper, people are being killed by mutated spiders, and wouldn’t it be great if someone — anyone — were to destroy any latent spider eggs before they hatch? Anyone, anyone at all. (Hint: it’s you. It’s totally you. You have to destroy the spider’s eggs.)

The Mutant Spiders doesn’t bother embedding items players need along their journey in its prose or even stash them in logical locations. Instead, you’ll discover a forest with things like saws, matches, rusty nails, lamps, and all sorts of helpful tools scattered around in piles between the trees. All things considered, it’s a pretty convenient forest to land in considering the task at hand. One frustrating limitation of the game is that players can only carry a finite number of objects and will quickly be prompted to start dropping old items to pick up newly discovered ones. These objects are often used in combination with one another and prior to playing through the game it’s nigh impossible to know which ones will work with others, meaning it’s extremely likely you’ll find yourself with some but not all of the items in your inventory needed to solve a particular puzzle with the other items discarded in a Hansel and Gretel-like trail in your wake through the forest. If I can provide any help at all it’s that every item only seems to have a single use. While logic dictates a machete would be an ideal item to hang onto in a world of mutant spiders, once you figure out where to use it, it’s safe to drop it. You won’t need your parachute or any discovered keys a second time. The game’s not big on callbacks.

If you like your vintage text adventures full of unfair and instant deaths, The Mutant Spiders is for you. Go the wrong direction from the beach and you’ll learn you don’t know how to swim, glub glub. Moving around in dark areas will result in a deadly head injury. Even worse are the instant deaths the game goads you into trying. One move after being informed I was getting hungry I stumbled upon some mushrooms. (They were poison.) After finding matches and some deadwood, I tried to light it. (The burns on my hand became infected and instantly killed me.) Adding insult to injury, you’ll die of starvation after 130 moves. I spent multiple games attempting to make a fishing pole (I had a branch and some wire), but like all of these old games, there’s no reward for coming up with alternate solutions to the single one the programmer had in mind. I tried every way I could think of to use my matches with the can of killer spray I found.

Oddly enough, the game’s most obvious enemy, the mutant spider itself, is the easiest to avoid. Progress far enough and you’ll encounter the spider wandering aimlessly and randomly from location to location. The spider will only attack you after remaining in the same location for three rounds. Players are way more likely to die from starvation, drowning poisoning, head trauma, or any other number of issues than be eaten by the titular arachnid.

A few of the game’s puzzles contain some pretty wide leaps of faith, and one of the few weblinks I found regarding this game contains a walkthrough hosted on the Classic Adventures Solution Archive. I honestly don’t know how anyone would have completed some of these old games, including this one, without assistance. The Mutant Spiders plays like a game in which we’re missing information, but if that’s the case you won’t find much help in the manual. The game’s documentation has been preserved by Plus4World, and it’s as scant as the game’s descriptions.

I once attended an evening pottery class and on display in the waiting room were several lopsided, misshapen, and non-symmetrical pot-like creations that, while resembling pots, didn’t quite make the cut. In the hall of text adventures, The Mutant Spiders would be on display in that same waiting room. While the game looks and plays like a classic text adventure, its sparse descriptions, awkward parser, thin plot and occasionally bizarre logic make it more of a text adventure curiosity than anything meant to be played for enjoyment. If navigating this game is the only way to save humanity from mutant spiders… prepare to be webbed.